“FUCK MEDIOCRITY” screams a framed print on the wall.

We’re startled, and then we grin. This isn’t the sort of thing you’d expect to see in an office in Kirulapona, much less the office of Calcey Technologies, a boutique software engineering firm with an expensive Silicon Valley client list and a very tame-looking website. Nevertheless, we’re at Siebel Avenue, Kirulapona, in the Calcey office, soaking in a set of colorful Startup Vitamins scattered strategically around the place.

The man who meets us here is like the poster: unexpected. Mangala Karunaratne, the founder and CEO of Calcey, is rather plainly dressed, alert and positively thrumming with energy. “That one’s my favorite,” he grins, gesturing at the poster before ushering us into his office.

His office is a strange duality. On the walls are photographs – a yak; a long, winding road; a family grinning up at the camera – his family, in fact. Just beneath the photographs sit an old, first-generation Macintosh, while at the other end, a sleek new Macbook sits happily on a desk – the old and the new making for a startling contrast. This is the present hunting ground of the man who went through the best and the worst of the dot-com bubble, living the Silicon Valley life, and later came back to Sri Lanka to build Calcey – a firm that now lists CompareNetworks, Wikimedia and Stanford University among its clients. The Macintosh? His father’s: one of the first two Macintosh computers to ever come to Sri Lanka.

“My father had a choice back then,” he says. “It was either two of these computers or a hundred acres of coconut. He chose to invest in the future.”

Mangala has had a varied career. The self-confessed adrenaline junkie graduated from California State University and dived straight into the dot com world. Like many others, he graduated smack in the middle of the dot com boom: every single graduate with a decent GPA wound up at one of the new web companies. Mangala cut his teeth in 1996 at golfweb.com, which CBS bought eleven months later. He moved onto Nortel, where he climbed the ladder until 2002, when Nortel became one of the most spectacular busts of the stock market crash.

It was a rockstar lifestyle: a life of unbelievable riches that came and were gone almost in a blink. They made unbelievable amounts of money, flew business class and didn’t think twice about spending a thousand dollars on night at the finest hotels.

But eventually, everything crashed, and so by the time Calcey came into being, Mangala had learned the value of careful spending. It was a reset in more ways than one. They started at an office in Maradana, a space once used by his father’s printing business. They bootstrapped everything – whatever they spent, they had to earn first.

“Honestly, I don’t think Sri Lanka will see a similar boom,” he says, when I ask about the rising tide of .lk startups. “We’re not India or America: we don’t have the numbers. But what we can do is take those lessons and apply to providing quality as opposed to quantity. There’s a huge opportunity.”

Calcey follows the same approach Mangala preaches – it’s a small, very professional firm that relies on quality than sheer numbers, strictly focused at a very specific market.

“It’s actually hard to hire engineers in the Valley,” he says. “Everybody there wants to work for the next Facebook, Twitter, the Next Big Thing. Small and medium companies which avoid massive VC funding and publicity find it hard to hire top engineers. That’s who we go after: we offer our skills and expertise there.”

Caley is relentlessly Agile: when on a project, they initially start hammering out an MVP – the Minimum Viable Product – which they show to the client so that things can be taken apart, discussed and the project modified. From there on, everything is a building and constant refining.

All of Calcey’s money is made this way – in Mangala’s words, “Wheels that churn and make money.” Sometimes, though, they get the chance to spin off their own products. He shows to us a system for facial recognition and fingerprint that has potential at airport security, and another that automates the entire printing process at companies – implemented at one of the largest printing presses that his family owns.

When asked about nightmarish projects, Mangala gets thoughtful. Sometimes things get tough, he confesses: Sometimes, during the process, a lot of deadlines and moving parts take an exponential amount of effort to get around and avoiding burnout takes a bit of juggling. “But I have to admit, every experience is a learning process. Every time, we discover new solutions and new ways of looking at things.”

And true to his Startup Vitamins posters, he’s is a huge believer in working every step of the way with the end user in mind.

“If you don’t have empathy with the end user, you’re not a software engineer – you’re just a coder,” he says dismissively.

“You might create a brilliant table, but if the edges are rough, the customer is not going to like it. It’s not enough for something to be a technical marvel: you need to understand who’s going to be using it and you need to polish relentlessly to make the whole experience better for that person.”

But how does one hire and forge a team that caters to the Valley? Two things: attitude – and ability to learn. Calcey’s team doesn’t look for paper qualifications – and, as Mangala points out, they specifically look for people who can learn new things. Often, newcomers cut their teeth on internal products before they’re placed into actual projects for clients.

“We don’t look for people who define themselves as being a ‘Java engineer’ or an ‘IOS engineer’. Some companies do that: we don’t. Right now we do a lot of business-oriented projects – an Android or IOS front-end paired to a huge backend, mostly based on the Microsoft Stack and Python. IOS is very much in demand in the Valley. Tomorrow, it could be something entirely different. If you say you’re just a Java developer, the next technology to come along is going to make you a dinosaur.“

What advice, then, would a Silicon Valley entrepreneur give a new IT graduate emerging from, say, Colombo or Moratuwa?

“I’m a big believer in startups,” says Mangala. “But, if you’re a new graduate, getting some experience, learning the industry, working with teams, is something that you really need – that’s invaluable experience that pays of whatever you do.

If there’s one thing I’d say needs to be improved in Sri Lankan graduates – it’s the soft skills. Knowledge is excellent, but communication, English speaking, the entrepreneurial mindset, a risk-taking mentality – these are things we can work on. You shouldn’t be so insecure about a job.

If you’re good enough, you shouldn’t have to worry about a job – in fact I should be worried about keeping you in the company. This is every CEO’s problem.

And when you do get into your own startup – right now, our industry is heavily focused on the mindset that you need funding, you need VCs investing, you need to fly high from day one. But if you look at Microsoft, Apple, Oracle, all the companies dominating the landscape today, none of these started with huge amounts of funding.

That’s one thing we need to do in Sri Lanka. We need little startups that start small and grow on their own. Everyone wants to attract a multi-million dollar investor, but that’s not the only path. In Agile development, we don’t target the massive goal right from the start – we target incremental steps and work our way upwards.”

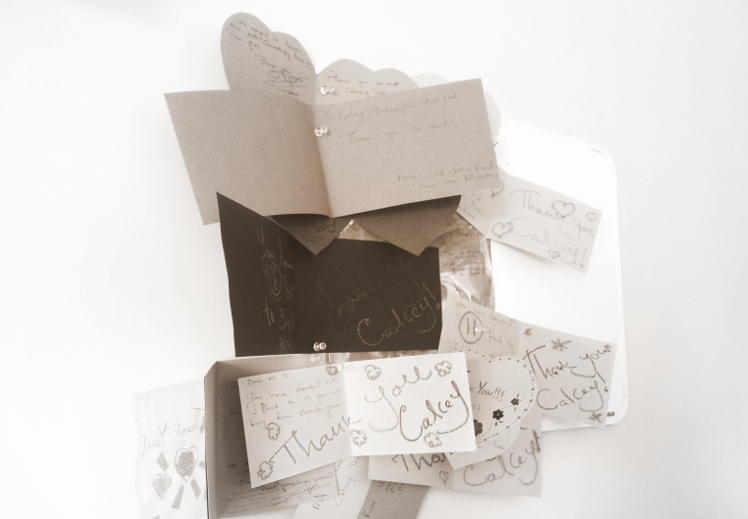

As we step out, we notice a strange sight: a motley collection of cards pasted to a wall. On them are written, in childish writing, “Thank you Calcey”. The words peek out from large cards, ornate hearts in pastel colors, small scraps of paper beating a tattoo of gratitude on the wall.

When I ask Mangala about this, he explains how, in cancer hospitals, little children who need chemotherapy have to undergo multiple, painful injections throughout their lifetime. In the States, hospitals would implant a small valve-like catheter over the heart, a single central device into which medicine could be injected and blood draws made, eliminating the need for hundreds of draws from the arms. Here, it’s just too expensive for many children to afford that kind of care. So every month, like clockwork, Calcey donates two of these valves to two needy children.

“We do what we can,” says Mangala quietly. “It’s good to give back to the world.”

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings