When social media was banned, almost overnight everyone in Sri Lanka transformed into digital ninjas. Those who didn’t know how to use privacy settings on Facebook suddenly knew what a VPN was. As racists broke curfew and stormed the streets, us ‘moderate’ minded people watched from the safe distance of a borrowed proxy.

Whether we care to admit it or otherwise, very little has been discussed about what Sri Lanka’s recent (and only official) social-media shut down really meant. Everyone knows of the ethno-nationalistic riots last month and how the Sri Lankan government responded. As usual, some reported it, others pointed out that the Government has failed and even made recommendations to fix it.

In Trademark Lankan style, we got international attention for all the wrong reasons. Here, we try to explore WHY the Sri Lankan government’s response, rather, reaction to the riots was a noble effort but nobler FAIL. More importantly, we explore what their response implies.

It didn’t work.

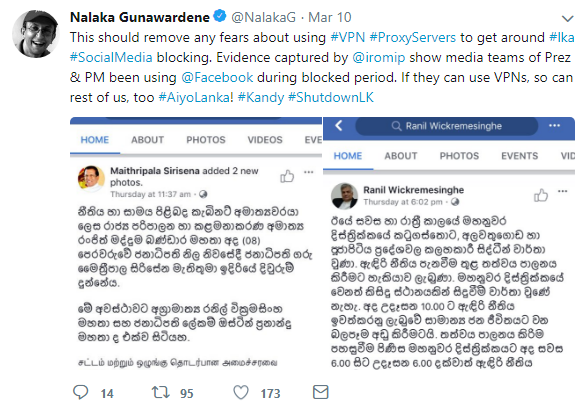

Author and data scientist Yudhanjaya Wijeratne has the numbers to prove it. According to his research, apart from damaging businesses which are heavily reliant on social media, Facebook wasn’t a ghost town. In fact, like the clever little short-cutters we are, we found a way to still get online on Facebook.

The President, Prime Minister and Harin Fernando – Minister of Telecommunications & Digital Infrastructure were some of them.

But what does all this really mean? Having been through the drill before, we know the President could easily activate the Public Security ordinance under Article 155 of the Constitution. This Ordinance brings a state of emergency into effect. The extent to which basic rights could take a back seat is not stipulated. Legally, therefore, the social media shutdown is NOT an infringement of your freedom of expression or access to information.

Before you get your knickers in a twist, this is how a lot of other technically advanced countries like the UK function. Even if we can argue that the UK only considered shutting-down social media it has heavy surveillance and wide-reaching authority to obtain information. This means the right to privacy is always potentially compromised in the interest of the community’s safety.

But what the UK has that we don’t is legal ways to challenge authority. One such mechanism is the concept of Judicial Review of administrative action. Since our presidency is executive in nature, even his action during the Emergency regulations cannot be questioned. So while the Tweet may be perfectly legal, it’s a bitter pill for the voters who backed a transparency-endorsing Yahapalanaya.

Since we know the ban didn’t prevent people from getting online, how implausible is the logic that it curbed rapidly mobilizing hate groups? In other words, what was the point of treating a symptom when the Government of Sri Lanka has been ignoring the root diagnosis all along? We don’t know if you’ve noticed but mobs have existed long before social media has- one could still use google maps without a VPN to email a specific location’s coordinates.

People still feel we pulled off a feat the US couldn’t. But public order takes more than Olympic medals and capitalism to maintain so we’re not sure this is a compliment. In our fight against ethnic violence, we have joined the likes of Algeria which shut-down Facebook to prevent cheating at an exam, Turkey which shut down Wikipedia in the paranoia of a reprisal of a political coup and Pakistan which has a government-censored version of YouTube following a 3-year ban.

Terrorists come in all shapes and sizes.

It doesn’t help that the Sri Lankan government failed to recognize the pol gedi when a pol gedi landed at their feet. By failing to categorize the riotous, curfew-breaking mobs as terrorists, the State inevitably looks like it pulled out a machine gun to swat a fly. Particularly since people in other countries face charges of terrorism for doing much less than breaking a curfew.

All the house-burning and mosque-stoning meant there was a real security concern. For those valiantly not downloading a VPN, this was enough to warrant a social media shut-down. But if we were not fighting terrorists, was the shutting down Facebook and the rest of social media an over-reaction? We’re not trivializing the lives and property lost in the riots, but simply saying it shouldn’t have happened in the first place.

Why? Because hate speech can get you arrested under Sections 219A&B of the penal code. It’s a little different from being arrested for physically hurting someone because the police need a legal warrant to arrest you for deliberately “wounding the religious feelings of any person…” either by words or actions. A less comforting thought is that hate speech has been freely wafting around on Facebook and the rest of the internet, long enough to be studied since 2014. Either no one is actively investigating these trends of hate speech online or is very bad at convincing a court to issue arrest warrants.

While we agree that Facebook needs to step-up their game, assertions implying the Sri Lankan Government has no tolerance for hate-speech is a little staged. Particularly since there have been repeated strong calls for the GoSL to take social media seriously.

Some hardcore Yahapalanaya-ers are probably going ‘well, putha, better late than never.’ For all they know (or care) the hate-groups were politically manipulated to affect local-government elections and the ‘boys did a good job’ at controlling the chaos. Our problem is, even if this was the case- our recent history doesn’t let the current government of Sri Lanka off the hook.

It’s not rocket science that a cocktail of hate-speech online and volatile ethnic fault lines is a stiff (like rigor mortis inducing) drink. Let’s call it the Red Lankan. The Economist observes that the Sinhala/Tamil fault-line has now moved to a new Sinhalese/Muslim one. But one must critically question if this eruption is as new and unpredictable for two reasons.

Firstly, ethnic fault-lines are exploited in Sri Lanka for votes. Politicians rely on tactics like ‘othering’ based on ethnicity to safeguard their seats. Somehow it doesn’t seem far-fetched to demand that policymakers clean up the mess they make when securing these votes. Secondly, one of the earliest issues between Sinhalese and Muslims in Sri Lankan modern history goes back to 1915, so it’s hardly a new problem.

Flinging dung at the ceiling is a fun game, simply switching off a ceiling fan won’t guarantee a splat-free zone. A failure to try those arrested as terrorists, we predict, will cause a rift in both fault lines since it will imply that terrorists only come from minority communities. There has been progress on this front since the arrests were made by the Terrorism Investigation Division. A little more publicity of this fact could potentially mitigate much of the animosity resulting from the few days we spent watching foreign adverts on Facebook.

Externally, we have bigger problems. The world is constantly running out of ways to keep up with cyber threats. Coordination and knowledge sharing to control technical breaches of security require trust between those reporting a breach and those acting to fix it. One way to encourage trust is through nationalized central points for incident management like National Computer Security Incident Response Teams (CSIRTs).

But shutting down social media to control a public nuisance is the virtual equivalent of the government that cried wolf. To a large extent, the legitimacy of measures like throttling internet bandwidth lies in who is behind those actions. For instance, a legitimate government may need to control the internet for public safety, but without that legitimacy to back it up, a government could easily be accused of possessing and using dual-use technology. Although the recent no-confidence motion didn’t fall through, it might cost us the trust of other NCIRTs and regional knowledge-sharing collectives.

It’s not a Kana-Mutti situation.

Hear us out, a good game of kana-Mutti is a team effort. You need a solid team to give instructions and someone who can follow those instructions, even when blindfolded. If you take a whack at the suspended mutti and miss, it’s hardly one party’s fault. In our case, we have the Sri Lankan government and the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission (TRC) calling all the shots, it is the Internet Service Providers (ISPs) that carry these instructions out.

Unfortunately, although Avurudu is upon us, the Sri Lankan government and the TRC along with ISPs are not playing a game of Kana Mutti. They’re in the business of running a country. Measures of cyber governance are slowly growing tired of excuses from businesses aiding surveillance (like social media platforms and ISPs.) It’s time we in Sri Lanka demanded our mobile carriers get more than just our monthly mobile bills right. For instance, Citizen Lab of the University of Toronto has proposed an accountability checklist to make sure the businesses involved in surveillance are monitored.

This is exactly what Kenya did last year. Authorities considered shutting down social media to prevent the spread of false election results and calls to violent opposition. Much like the ethnic fault lines in Sri Lanka, Kenya suffers from colonially-inflicted tribal fault lines. Post-election violence in the previous presidential election alone (2007) caused 1,100 casualties.

Yet, an article published before the August 2017 elections, demanded that Telcos and ISPs adhere to the UN Guiding Principles on Businesses & Human Rights. Particularly when the legitimacy of the government itself is highly contested, they were asked to keep the internet on.

Should our ISPs have done more? Perhaps many agreed with the Sri Lankan government’s decision since something had to be done about the angry mob. They may not have had enough information to scale the true extent of the situation. But these excuses are dated.

We’re not recommending that Telcos suddenly employ soothsayers to predict where the next ethnic tension will break-out. Actually, they don’t have to since we already have a system in place to ring the warning siren. SLCERT (Sri Lanka Computer Emergency Response Team) acts as the National Co-ordination point of all breaches of cybersecurity. Additionally, The Computer Crimes Act 2007 and Sections 219A &B of the Penal Code allows SLCERT to monitor hate-speech online.

No, it doesn’t mean if you sneeze online the SWAT team will materialize at your door. Although SLCERT is wholly owned by the government, it is registered as a private company, a subsidiary of the ICTA. We also would like to reiterate that the police alone can’t wake up and decide it feels like a good day to decide who is guilty of spewing hate-speech. They would still require a Court-issued warrant.

Concerns that criminalizing hate speech will result in a culture of self-censoring aren’t necessarily negative. If people in Sri Lanka know that hate-speech will be investigated, they may finally start thinking twice before either spreading fake news or liberally sprinkling racism all over the place. To make sure that the authorities stick to investigating only hate-speech, some simple steps could be easily put in place. For example, a precise framework governing the conduct of ISPs, SLCERT and their partnership could be published.

Conclusion:

While the social-media ban feels unfair it’s not an infringement of democratic rights. We know that our presidency in Sri Lanka is executive. Allowing the Sri Lankan government to control the internet off and on is a privilege we constitutionally give our policymakers when we vote for them. Instead of mourning the demise of ‘democracy’ it might help to look at things we can do. We can start with questioning the tactics policymakers use to get their votes.

If we don’t call out our government’s BS, no one else will. Being angry at FB’s casual approach to community standards is great. But unless we show our government that we’re not okay with their relaxed/poorly strategized plans, nothing will change.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings