“And this is where we handle all the billing,” said Asanga Ranasinghe, IT manager at Hutch Sri Lanka, gesturing at a cabinet that stood about seven feet high. Rows of blue lights blinked hazily inside.

I stared at it. It didn’t seem very impressive. “All of it?” I asked.

“All of it.”

“So what if I press this button here?”

“You’ll shut everything down. Don’t press that button. Come away.”

“All of it.”

“So what if I press this button here?”

“You’ll shut everything down. Don’t press that button. Come away.”

I shuffled away.

(photos by Ushan Gunasekara. There’s more on our Facebook page.)

We were inside a large, white and almost completely hidden building tucked away in the sleepy village of Walpola, a little distance away from Ragama. Scattered across Sri Lanka are buildings like these. They belong to the various companies that provide voice, data and messaging services to the public – SLT; Dialog; Hutch; Airtel; Mobitel; Lankabell; Airtel; you name them. Unlike the Galle Road offices, these buildings are kept very much away from the public eye: almost hidden, one would say.

For a good reason. Here, inside these buildings, lie the machines that transfer a call to its destination, a message to your girlfriend, a URL to its recipient; the systems that assign numbers, manage your bills, track and see whose phone is busy, whose phone is switched off, and who’s out of service area.

You get the picture. Forget the headquarters with the girls in heels and banners of services that nobody really wants; it is these almost-hidden data centers that are the beating heart of any telecommunications company. Take these out and all the public communication within a network grinds to an immediate halt. The only indicator to the outside world is that these centers usually have a huge tower right in their midst.

Of course, getting inside one is a bit tricky, since nobody wants a bunch of guys poking at random critical infrastructure and going “oooh”. Eventually, however, we managed to convince our Internet partner, Hutch Sri Lanka, that it might be worth it to let us drop by for a visit; with some reluctance, they agreed. And so here I was, eye-to-eye with the machines that actually did the dirty work.

Some of the work, anyway.

When you make a call, or send a text (or even access a URL) your phone broadcasts radio waves that are picked up by the nearest tower. The tower then throws your call to a switching center. Your call – or message – is then analyzed. What type of request is it? Who is it coming from? Where should it go to? How much should you be charged? All of this is determined by the machines that lie deep in facilities like these.

Here, in the case of Hutch, is a room kept at a very cold temperature. Copper strips crisscross the walls and ceiling; this place, like many others here, is a giant Faraday cage, keeping most electromagnetic radiation away from rows of tall, silent towers that sit here in the darkness.

Galle TRAU-31 , reads a huge box with a ZTE logo; TC-Kandy 22, reads another.

Unfortunately, no photography is allowed here, so words will have to suffice. We duck in among cables, led by Janitha Mendis, the engineer burdened with helping us understand how this all works.. To one side sit squat gray ZTE cabinets, their electronics inert: decommissioned leftovers from the 2G era. To the other side stand looming black Huawei systems, humming with activity: the newer systems, bought when the network switched 3G.

Here are the IP clocks, which synchronize time across all devices on the network: here is the universal media gateway, which detects when you’re trying to reach a number on another network and transfers your call accordingly. A five-foot tall fire extinguisher sits in the darkness, looking almost comically out of place among the rows of electronica.

When a call or an SMS comes in, explains Janitha, many processes kick into action. Firstly, there’s the rather technical tasks of wireless transmission and the collecting and input of all the signals thrown out into the Hutch network.

Then the request is routed through a smaller set of servers in a smaller room. These examine the account behind the order and see if it has the necessary balance for the transmission start. It then makes its way here, where the big machines hum ceaselessly. They figure out what has to be done, which data has to be sent where, what numbers have to be pushed to make things happen. This room is essentially a giant junction, with connections to every part of the network. Galle, Matara or Kandy is just a few bytes away.

In the next room are racks upon racks of terribly fragile-looking silver nodes. Each row is connected to a miniscule circuit, and fiber optic cables lead in and out all of them. This is the connection to Anuradhapura right here.

These systems grow, of course. As more subscribers are added, upgrades happen. In the case of the billing servers out front, more and more hardware is piled in on an as-you-need basis – in fact, as we walked in, a group of technicians were installing yet another machine.

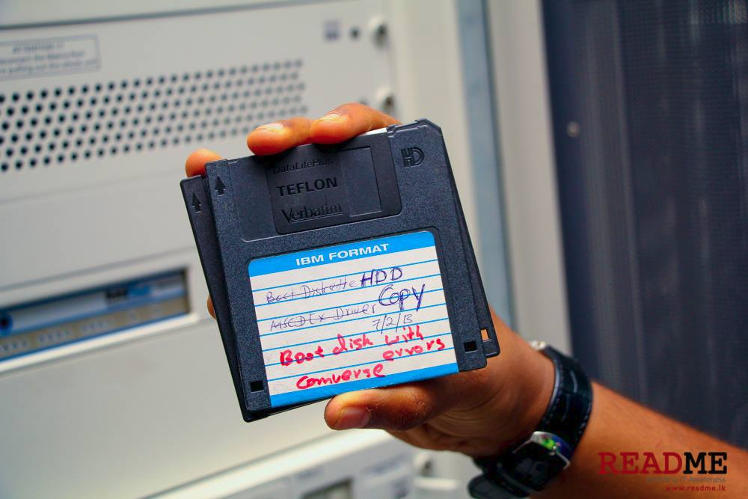

The result is that you see a huge range of hardware, all the way to the latest of what HP has to offer to machines two, five, even ten years old. New hardware is brought in and the old hardware is decommissioned and kept in there for both safekeeping and redundancy. In fact, there’s even a solitary Pentium Pro tucked in one corner – for sentimental reasons, as Asanga puts it.

In the main room, things are a bit different. Licenses must be bought for the Huawei systems to expand: along with these licenses come new add-ons that bring more power to the network. Anything not used is outright shut down: they take up a lot of power.

In fact, powering these things is no joke. When we were shown into another Farady-caged room housing UPS units that came up to our waist, we were skeptical. But then we were led downstairs, to where things get a lot closer to the ground.

Here, surrounded by the smell of ozone, were two generators – one to back up the other. It’s rare for CEB grid to lose power here, but should that happen, the main generator can cut in within a minute, restoring power to the one line that snakes off to the server rooms.

To power the complex takes a staggering effort: the generator sucks in some 70 liters of fuel per hour, pumping out the 300-odd kilowatts required to keep the complex operational at peak capacity.

Backing this system up – taking up that one minute of downtime – is yet another room filled with racks of 48 volt DC batteries. The batteries are connected directly to the main line that that carries power to the servers. When there’s power, the batteries charge: the minute the line loses power, the power in the batteries dissipates back into the line, keeping it fed until the generator can come online at the other end. The speed of this man-in-the-middle lies in its simplicity.

“If there are no batteries, the whole network goes down for one minute,” says Rukmal Piyantha, electrical engineer. “One minute is enough for us to get the power running. But to be safe we can provide eight hours of backup from these.”

Heading back from this place is a melancholy affair, because it takes us past – and underneath – the tower that actually collects all these signals and retransmits them. All around it lie bruised and damaged metal antenna pods, some of them taller than I am. They’ve been felled by all manner of things – failure, lightning strikes – and now they sit around the tower like a metal elephants’ graveyard of sorts.

On the way out, we run into Asanga again. He’s seated in a room overlooking the approach from the gate to the building, sipping Nescafe. On the walls are mounted monitors switching rapidly between different graphs and status indicators. This is where the whole operation is monitored.

“What would really have happened if I’d pressed that button?” I ask him.

“Like I said,” he says calmly. “You’d have knocked out our billing system. But you didn’t. Coffee?”

Last thing we want is to have an elephant accidentally shutting down my internet!

Not though the elephant knew

Someone had blundered

Theirs not to reason why

Theirs but to know down your Internet and die

– Tennyson

Very informative and really interesting to read. Good one bro.!