Freedom House has evaluated that Sri Lanka’s internet freedom reduced in 2022, compared to 2021, “as the government sought to repress historic protests.” An independent research and watchdog organization on democracy and freedom, Freedom House recently published its ‘Freedom on the Net 2022’ report which saw Sri Lanka’s overall internet freedom receiving a score of 48/100, a decline from last year’s 51/100.

The Aragalaya on the internet

This year’s vast citizen mobilization (‘Aragalaya’) that happened across the country against the now-ousted-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s administration was partly mobilized online. Noting this, Freedom House said that the internet was an avenue for digital activism and engagement about political issues in Sri Lanka. However, online organizers were arrested and new criminal penalties were imposed for mobilization via social media.

The use of hashtags to express dissatisfaction with the former administration was prominent, with ones such as #powercutlk, #economiccrisislk, #GoHomeGota, and #පන්නමු tracking the online discourse over the year. This online mobilization reflected the massive offline protests that took place, including the months-long protest site at Galle Face Green (‘Gota Go Gama’), outside the Presidential Secretariat.

Despite the success of the online mobilization this year, the report said that previous online campaigns had only “uneven progress in achieving their goals.” Previously, hashtags were used to discuss the Easter Sunday terror attacks, disappearances that occurred during the civil war years, detentions under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), and as of just last year, ‘#MeToo’ to discuss the harassment of women in workplaces in the media industry.

Raisa Wickrematunge, an independent researcher who contributed to the study from Sri Lanka spoke to ReadMe about the significance of this year’s study.

She highlighted that Sri Lanka’s internet freedom declined in a few key areas from June 2021 to May 2022. She said that part of the reason for the decline was that the Government used a range of measures to try to prevent protesters from mobilizing in response to the economic crisis.

“This included blocking Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Viber, WhatsApp, and Telegram in April for 16 hours ahead of key protests, arresting activists who were mobilizing online (including an administrator of the #GoHomeGota Facebook page), and the declaration of states of emergency in April and May. The states of emergency made sharing information considered false or that might “cause public alarm” or “disorder” an offense, potentially impacting social media users who posted about ongoing protests.”

In July, right before the historic 09 July protest took place, a letter circulated on social media, claiming to be from the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission of Sri Lanka (TRCSL), directing telecommunication providers to block all services except voice calls on 09 July in Colombo. Although TRCSL Chairman and Technology Ministry Secretary Jayantha de Silva claimed that the letter was false, ReadMe reported at the time that industry sources had confirmed the authenticity of the letter.

“Government restrictions on the online space during times of tension (the social media blocks and emergency regulations) were supplemented with measures like imposing a curfew or using the law to restrict people gathering for protests. This is an indication that the government recognizes the potential of online spaces to organize and to discuss issues online,” said Wickrematunge.

Continued trends

Wickrematunge said that internet users, including journalists working for online platforms, were arrested, detained, or intimidated for their online posts related to the protests, as well as for highlighting shortfalls in the Government’s response to Covid-19.

The report pointed to instances of harassment endured by the Media.lk Editor Tharindu Jayawardhana and Hiru TV Presenter Chamuditha Samarawickrama over the past few months. It also highlighted that in September 2021, a teenager was asked to report to the Criminal Investigations Department (CID) for his Facebook activity. In January 2022, a woman’s phone was examined by the CID for sharing a post about former President Rajapaksa being hooted at, while in February 2022, Manorama Weerasinghe was also summoned to the CID.

“This is a continuing trend in that internet users and especially social media users have been routinely arrested, detained, or intimidated in previous years as well for their online posts. Another notable incident was hacktivist groups attacking government websites and breaching government databases in solidarity with protesters.” Wickrematunge said that the hacktivist groups could have been ‘Anonymous’ and possibly, the Tamil Eelam Cyber Force, although these were never proven.

“This too is a continued trend in that groups like Tamil Eelam Cyber Force routinely attack government websites around key dates (especially Remembrance Day marking the end of the war on May 18),” said Wickrematunge.

ReadMe tracked an alarming number of government and private websites in Sri Lanka which were subject to cybersecurity breaches in recent years. These incidents show the need for cybersecurity awareness and practices, particularly at a time when the country evolves in its digitization attempts.

Access to the internet

This year’s economic crisis was the worst that the country recorded since its Independence. One dire consequence of this was the fuel shortage which severely impacted thermal power stations in the country, depriving the public of electricity for almost 13 hours per day during the peak of the power crisis in March of this year. The report said that this led to increased obstacles to internet access.

This increased restricted access to internet connectivity occurred despite former President Rajapaksa’s promises to deliver 5G mobile broadband coverage countrywide. The State-owned Sri Lanka Telecom (SLT) reportedly spent about USD 7.3 million on 5G-related technologies as of December 2021 although its rollout may be delayed past 2022.

The report said that the urban-rural divide too played a role when accessing the internet. The Western Province has the highest percentage of households accessing the internet, an indication of the infrastructural advantages possessed by the Province’s urban areas, including Colombo. Government statistics found that in the first half of 2021, over 45% of Western Province residents were computer literate. On the other hand, only 29.1% of Northern Province and 28.9% of Eastern Province residents were computer literate in 2021 – two provinces that faced delayed infrastructure development due to the civil war. However, Freedom House said that telecommunications infrastructure had recently developed in these provinces, with a steady growth in internet usage.

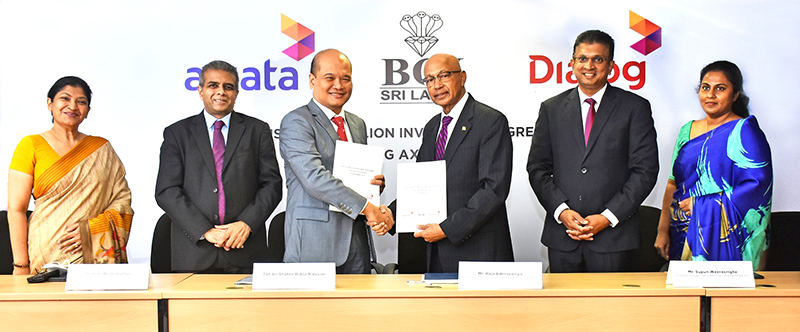

Just over a month ago, Dialog Axiata announced an investment of about USD 152 million to develop the country’s telecommunication infrastructure, particularly to cover the rural and deep indoors. This followed in the footsteps of TRCSL’s announcement to completely shut down the 3G network. Dialog has also taken the lead in South Asia in trialing 5G networks – in 2018, it piloted the first standards-based 5G fixed-wireless pilot transmission and deployed the subcontinent’s first 5G trial network in 2020. However, Sri Lanka is yet to auction the 5G spectrum despite a statement by former Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa in 2021 about plans to do so. Neighbour India recently auctioned its 5G spectrum to reportedly raise about USD 19 billion.

Sri Lankan students had to adjust to online education for most of 2020 and 2021 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. However, questions of equitable access to e-learning remained, especially as a survey from 2019 showed that only about 34% of households with children had an internet connection. Freedom House highlighted that the Education Ministry had also warned in early 2021 that only about 30% of the student population had access to or could effectively afford remote education during the pandemic. The Department of Census and Statistics showed that only 22.9% of households owned a desktop or laptop in 2021.

‘Independent’ regulators

Importantly, Freedom House assessed that national regulatory bodies, including the TRCSL lacked independence and often failed to act fairly. Freedom House said that this was compounded when former President Rajapaksa brought the TRCSL, SLT, and the Information and Communication Technology Association (ICTA) under the Defence Ministry in May 2022. They further noted that successive regimes used political allies to head the TRCSL.

“A former chairman, Jayantha de Silva served as Secretary to the Technology Ministry between June and August 2022. A former Director General, Oshada Senanayake, publicly advocated for a Gotabaya Rajapaksa presidency when speaking to a convention of academics and professionals,” said the report.

However, following the countrywide social media ban in April, Senanayake resigned from his position as Chairman of ICTA, saying that he stands by his “principles and ethos.” His resignation as TRCSL Director General was a few months before that, in December 2021.

Manipulated media

Freedom House highlighted that during the protests, researchers had found that proxy accounts and Facebook pages associated with, or supportive of the Rajapaksa family, spread content discrediting the protests. A recurring concern in Sri Lanka, a previous example was in October 2018 when former President Maithripala Sirisena unconstitutionally appointed Mahinda Rajapaksa as his Premier. The public received dangerous messages on social media, legitimizing the coup.

Though it’s not just limited to Meta’s platforms. Sri Lankan Twitter has also seen targeted, politicized social media campaigns – Groundviews found in 2017 that a troll army constantly pushing content against it was overwhelmingly promoting the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) MP Namal Rajapaksa.

Furthermore, research from July to December 2021 showed politically motivated false information campaigns on Facebook and WhatsApp, targeting activists and left-wing opposition parties. An Oxford Internet Institute report published in 2020 said that evidence showed that Sri Lankan teams worked to support preferred messaging, attack the opposition, create division, and suppress critical content.

Challenges and importance

Wickrematunge said that the overall aim of the project is to evaluate to what extent a rights-enabling online environment is fostered in a particular country, recognizing that internet freedom can be affected by a range of actors, including States and technology companies.

“It is hard to find reliable statistics on Sri Lanka’s internet penetration but it is clear that year on year, more Sri Lankans are accessing the internet (especially through smartphones),” says Wickremetunge. The ‘We are Social’ report shows that the number of internet users increased by 528,000 in January 2022, compared to the increase of last year’s 800, 000 users. TRCSL data shows that there were 21.8% more mobile broadband connections in June 2022 than last year.

“While there are still barriers to accessibility, especially outside urban areas, the digital space in Sri Lanka still allows people to discuss issues, read the news, and, as we saw this year, mobilize for protests. So tracking how the online space is regulated is important and relevant for Sri Lankans.” Wickrematunge emphasized that the continued attempts to regulate the online space indicate that consecutive governments recognize the growing importance of online spaces in Sri Lanka.

Regulating the online public sphere remains a controversial question and a heavily contested topic in modern democratic concentrations. Finding a balance between internet safety and the protection of fundamental rights, including the freedom of speech, remain a vital concern for many governments across the world. Tech giants too are tasked with attempting to find social responsibility in the face of massive profits while ensuring customer trust.

Although the internet is regarded as being revolutionary, there is a question of whether positive social change can be effectively brought about through it. As Freedom House shows, the space for online freedom declined over the past few months. This occurred even as the entire country watched people find a voice online to express their dissatisfaction with the once-popular Rajapaksa-led administration and against the corruption of politicians. Sri Lanka has both witnessed the weaponization of online spaces for division and communal hatred and seen the effective use of social media to stand up to an authoritarian regime this year. If we regard the internet as a tool, then we must protect the freedoms we have on it – just like in any other space – to enhance our collective voice and accountability.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings